(This page contains excepts from WIKIPEDIA)

Desaparecidos (Spanish for “disappeared,” pronounced [des.a.pa.ɾe.ˈθi.ð̞os], in Latin America [des.a.pa.ɾe.ˈsi.ð̞os]) is a term commonly used in many Central and South American countries to describe people who were secretly arrested or abducted by state or quasi-state security forces and subsequently tortured and murdered. Based on this original meaning, the term has also been increasingly used in Spain in recent years to refer to victims of the Franco dictatorship.

The term derives from the practice, common from the 1960s to the 1990s under military dictatorships, particularly in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Uruguay, of making political opponents or even just undesirable individuals disappear. In these cases, the victims are arrested or abducted and taken to a secret location. Relatives and the public are kept in the dark about the sudden “disappearance” and the whereabouts of the missing person. The victims are usually murdered without trial after a short to several-month period of detention, during which they are typically subjected to severe torture. Their bodies are then disposed of. Because the murders are generally kept strictly secret and state authorities vehemently deny any involvement, relatives often remain in a desperate state of hope and resignation for years, even though the victim was frequently killed just days or weeks after their disappearance.

According to estimates by human rights organizations, Latin American military dictatorships caused the permanent “disappearance” of approximately 35,000 people in this way during the 1970s and 1980s as part of so-called “dirty wars.”[1] The prosecution of these crimes only began in many of these countries around the year 2000 and continues to this day.

The Dirty War

A dirty war, also sometimes called a squalid war[1] (Spanish: guerra sucia, English: dirty war), is a conflict in which state security forces use systematic illegal and human rights-violating methods against internal political opponents, separatist, terrorist, religiously motivated, or other resistance movements. Generally, the countries involved are not engaged in a regular or undeclared war with an external enemy; rather, the term indicates the massive scale of illegal violence used by the state against its own citizens or those of a territory it occupies. In military and intelligence terminology, these are considered counterinsurgency operations, which fall under the umbrella of asymmetric warfare. These conflicts are also referred to militarily as low-intensity conflicts.

The waging of dirty wars against political opponents or resistance movements is primarily a characteristic of dictatorships, especially military dictatorships, and authoritarian states. However, there are also well-documented examples of Western democracies conducting conflicts in this manner. Such conflicts, typically involving systematic crimes against humanity, occurred particularly frequently in Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s. With the end of the Cold War in 1990, they became less frequent, as they had often been considered proxy wars in the East-West conflict. The United States, in particular, had made considerable efforts to combat the advance of socialist and communist resistance and guerrilla movements into developing countries, especially in Latin America and Southeast Asia. This was based on the premise that these movements were viewed, within the framework of the domino theory and the rollback policy, as a potential threat to US security and detrimental to American economic interests (see also the Reagan Doctrine). More recently, Russia’s two Chechen wars and various aspects of the US-led War on Terror have been described as dirty wars, particularly certain practices of the US military in occupied Iraq.

Characteristics

The methods employed include arbitrary arrests, detention without legal basis, and enforced disappearances,[2] the use of torture,[3] and extrajudicial killings.[2] Also among the methods are the toleration or support of paramilitary groups and death squads[4][5] that operate outside the law, and the support or instrumentalization of terrorist groups[6] by the government of the country in question. In connection with the systematic, illegal use of force by the state against civilians in its own or an occupied country, the two American political scientists R.D. Duvall and Michael Stohl proposed the term state terrorism.[7]

In these cases, the line is regularly crossed into the arbitrary oppression and terrorizing of large segments of the civilian population. Amnesty International commented on this in its 2003 Yearbook on Human Rights [Note: most of the examples mentioned are explained in more detail below] as follows:[8]

“In the ‘wars’ against political opponents of all kinds, human rights such as the right not to be tortured, the right not to be arbitrarily arrested, and the right to life have been violated. The victims of these violations have often included segments of the population who have not engaged in any illegal activities whatsoever. Some examples include the ‘dirty wars’ in Latin American countries such as Argentina and Chile in the 1970s, South Africa during apartheid, Turkey, Spain, and the United Kingdom with regard to their treatment of nationalist minority movements, the high level of political violence in some Indian states, and in Israel to this day.”

Crimes Against Humanity

In 1976, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told representatives of the Argentine military dictatorship that he hoped they would “bring their terrorism problem under control as quickly as possible.” The Argentine foreign minister, who had expected sharp criticism of his government’s human rights violations,[9] was in a “euphoric mood” afterward.[10] Over the next seven years, the military murdered up to 30,000 people in what they themselves called a dirty war.

The systematic practice of illegal killings—sometimes referred to as state-sanctioned murder, mass murder, or genocide,[2][11] depending on the scale—as well as enforced disappearances and torture constitute crimes against humanity under international law.[2] The waging of dirty wars is primarily a characteristic of military dictatorships and authoritarian states. However, there are also well-documented examples of Western democracies conducting conflicts in this manner.[6][12][13]

In 2002, the Rome Statute, an international treaty, entered into force. For the first time, it defined a wide range of crimes against humanity, including those mentioned above, as internationally prosecutable offenses. The Statute forms one of the legal bases for the jurisprudence of the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Some states, including the United States, do not recognize the Court. For example, the Bush administration demanded immunity for US citizens, which the Court refused to grant. In response, the American Service Members’ Protection Act came into force that same year. This act implicitly authorizes the US president to order the military release of US citizens if they are required to appear before the International Criminal Court in The Hague. It also prohibits US authorities from cooperating with the Court. Because of the implicit threat of invasion by US troops, critics have also called the law the “Hague Invasion Act.”[14]

Furthermore, the law allows for the withdrawal of US military aid to all states that are not members of NATO and have ratified the Rome Statute under international law. By 2003, the US had concluded bilateral agreements with more than 50 states intended to prevent the extradition of US citizens from these countries to The Hague. Also in 2003, military aid was withdrawn from 35 states that refused to sign such agreements.[15]

Argentine Military Dictatorship 1976–1983

→ Main article: Argentine Military Dictatorship (1976–1983)

In 1977, German social worker Elisabeth Käsemann was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by Argentine soldiers, like tens of thousands of other Argentine victims of the military dictatorship. Her volunteer work in the slums of Buenos Aires had made her a suspect, labeling her a “subversive,” meaning a critic of the regime.

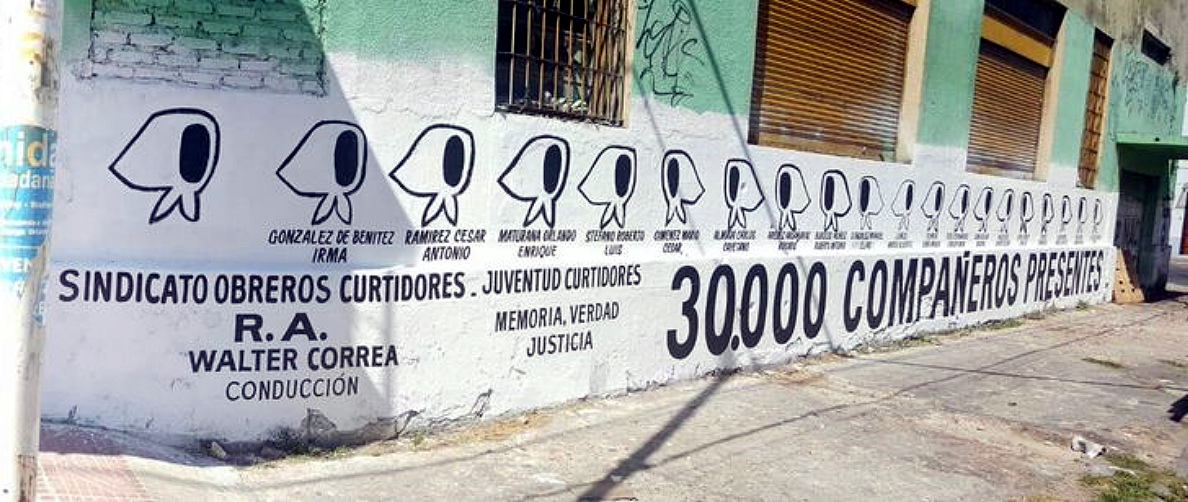

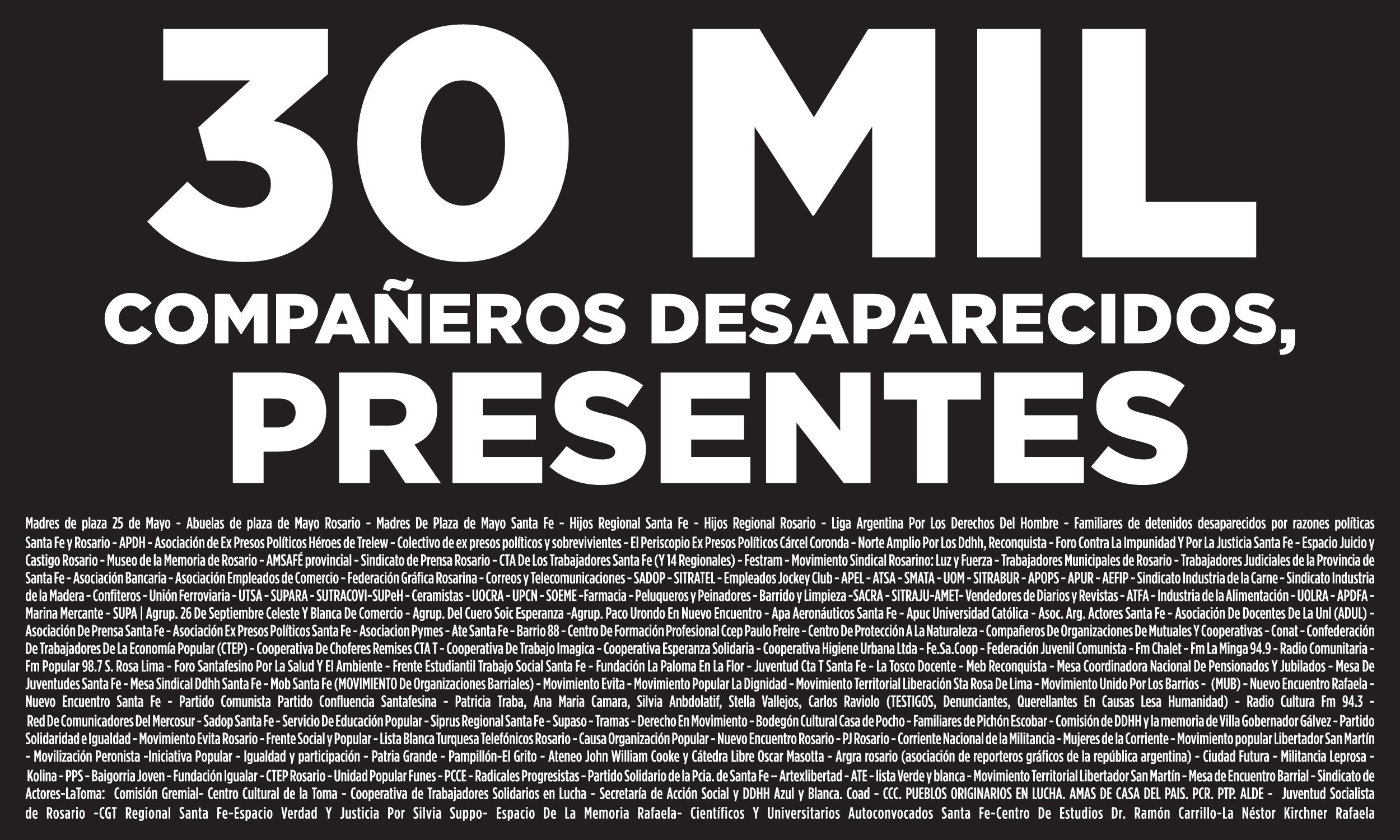

During the so-called Process of National Reorganization, the Argentine military dictatorship waged a dirty war against all kinds of political opponents, resulting in the deaths of up to 30,000 people. In this case, the term was used by the military itself.[2] Similar events took place in almost all Latin American countries during the 1970s and 1980s, including Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. The overall toll of Latin American repression policies during this period is estimated by human rights organizations to be around 50,000 murdered, 350,000 permanently disappeared (“desaparecidos”) and 400,000 imprisoned.[37]

Historical and Political Context

The enforced disappearance of political opponents has been and continues to be practiced in many countries worldwide – mostly those governed by authoritarian or dictatorial regimes. The cases in South American countries are particularly noteworthy because the phenomenon emerged in the majority of South American countries within a relatively short period, and the affected states were ruled by right-wing military dictatorships of a similar type. Furthermore, at least six of these countries – with proven, though still not fully clarified, support from the USA – cooperated within the framework of the multinational intelligence operation Operation Condor, in which they assisted each other in the persecution and illegal killing of political opponents. The enforced disappearance of people has been defined as a crime against humanity under international law since 2002.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the era of Latin American military dictatorships, almost all of which had been supported by the United States, gradually came to an end. The injustices previously committed against the disappeared were, for a long time, only inefficiently or not at all prosecuted under pressure from the still-powerful military in the fledgling democracies, leading to considerable disappointment and bitterness among the bereaved. Only from the 2000s onward did an effective legal reckoning begin in several countries, with numerous trials being initiated and many perpetrators now sentenced to long prison terms – including a number of torturers from the lower ranks of the military, but also several junta generals who had commanded the regimes at the time. The process of coming to terms with the past is not yet complete; many trials are still ongoing. Some older perpetrators, mostly from the higher ranks at the time, were able to escape punishment due to old age or death, such as the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

Background

In the second half of the 20th century, many Latin American military dictatorships based their violent repression on a new technique of repression, carried out in strict secrecy and known as enforced disappearance (desaparecidos forzada). This largely replaced the previously quasi-official torture and murder of regime opponents. It was based on the doctrine of National Security, also propagated by US military strategists, which defined the enemy to be eliminated as being within society (enemigo interno). Thus, the circle of supposed enemies of the state was expanded from armed groups organized in guerrilla units or communist movements to include large segments of the population. This redefinition of the term “enemy of the state” to encompass any subversive person deemed undesirable by the regime amounted to a repressive infiltration of the entire society, in which almost anyone could become a victim. A quote from the governor of Buenos Aires province, General Ibérico Saint Jean, in 1977 is particularly indicative of the consequences of this strategy:

“Primero mataremos a todos los subversivos, luego mataremos a sus colaboradores, después […] a sus simpatizantes, enseguida […] a aquellos que permanezcan indiferentes y finalmente mataremos a los tímidos”

“First we will kill all the subversives, then their collaborators, then their sympathizers, then the undecided, and finally the timid.”

In Argentina, the authorities referred to their actions as a dirty war (guerra sucia) against so-called subversion. The origins of enforced disappearances in Latin America can be traced back to the mid-1950s, following the CIA-organized coup against President Guzmán in Guatemala. They were practiced there almost continuously until around the turn of the millennium.

A text by the Heinrich Böll Foundation described the issue as follows:

“Ideologically armed with the doctrine of national security, also inspired by the USA, Latin American militaries justified their claim to a central role in state and society from the 1960s onward. They saw themselves as the only force capable of governing the nation-state. The military dictatorships assumed control over national development and internal security. This was legitimized by the construct of an ‘internal enemy’ who, in defense of ‘national interests,’ had to be physically destroyed and against whom large segments of the population had to be controlled.”

Arrest, Torture, and Murder

In 1976, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told representatives of the Argentine military dictatorship that he hoped they would “bring their terrorism problem under control as quickly as possible.” The Argentine foreign minister, who had expected sharp criticism, was in a “euphoric mood” afterward.[3] Over the next seven years, the military murdered up to 30,000 people, most of whom they made disappear without a trace.

In practice, enforced disappearance meant that people were arrested from everyday situations or at night by anonymous members of security forces (military, secret police, intelligence services) without explanation. The arrests were usually carried out quickly, discreetly, and in secrecy, so that the reasons for the person’s “disappearance” remained unknown to their relatives. Since they didn’t know whether and which state authorities were holding their family members captive, or whether they might have actually “disappeared” for other reasons, the searchers often embarked on a desperate odyssey through police stations, hospitals, and prisons. It’s important to note—to understand the situation of the relatives—that the Argentine dictatorship, for example, consistently denied having anything to do with these disappearances until the very end of its rule. Because the courts were also tools of the respective dictatorships, the relatives were completely powerless against this practice and often had no choice but to resign themselves to their fate after years of searching, unless the victim’s body was eventually found or, in rare cases, they were finally released. In Argentina, it was common for the parents of young men to be told by authorities, with a wink and a smile, that it was well known that young men often fled abroad if they had “accidentally” impregnated a woman.

Typically, those abducted were held and tortured for several days in military bases or civilian locations such as abandoned auto repair shops until they were killed. This provided an unlimited number of informants, whose tortured interrogations generated new names of suspects. The state could then dispose of the life or death of the perceived enemy without having to engage in lengthy legal processes or face national and international political accountability. The bodies of the disappeared were either buried in anonymous, secret mass graves (for example, in Chile), thrown into the sea (Argentina), into volcanoes (Nicaragua), or into rivers, or left along roads, in university buildings, chimneys, and other public places. In Argentina, the Naval Technical School (Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada) in Buenos Aires was one of the main centers of repression. It is estimated that around 5,000 people were tortured there and subsequently murdered—with the exception of approximately 200 survivors.[4]

As early as 1977, on the first anniversary of the Argentine dictatorship, the Argentine writer Rodolfo Walsh wrote from the underground in his Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta:[5]

“15,000 disappeared, 10,000 imprisoned, 4,000 dead, tens of thousands expelled from the country—these are the stark figures of this terror. When the conventional prisons became overcrowded, they transformed the country’s largest military installations into veritable concentration camps, to which no judge, no lawyer, no journalist, no international observer has access. The application of military secrecy, declared indispensable for investigating all these cases, effectively turns the majority of arrests into kidnappings, allowing for torture without any restrictions and executions without trial.”

On May 17, 1978, the daily newspaper La Prensa (Buenos Aires) published the results of investigations by the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights (Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos), founded in 1975: a list of 2,515 names of “disappeared persons.” In the case of 1,318 of these “disappeared persons,” the authorities had officially informed relatives who had inquired about the whereabouts of those arrested that they knew nothing about their whereabouts. There was no response from the authorities regarding the remaining 1,197 women and men, but the documentation of these cases by the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights indicated that they had been “taken away.”[6]

As revealed by the testimonies of former military personnel, many Argentine disappeared persons were thrown alive and naked from military aircraft over the open sea after being drugged. A plane carrying ten to fifteen prisoners took off regularly every Wednesday. Approximately 2,000 people are believed to have died in these “death flights” (Vuelos de la muerte) over a two-year period.[7] The Argentine public reacted with particular shock to reports that the perpetrators were regularly given spiritual support by military chaplains. These chaplains had downplayed the acts as a “humane and Christian way of killing.” The events came to light in 1996 through a book by the well-known Argentine journalist Horacio Verbitsky, which was based on interviews with former naval officer Adolfo Scilingo.[8] Scilingo was sentenced to a long prison term by a Spanish court in 2005, partly based on his testimony to Verbitsky. During the trial, he denied the crimes and claimed to be innocent.

Psychological Devastation

Memorial march with photos of the disappeared on the thirtieth anniversary of the military coup in Argentina, March 24, 2019.

Particularly distressing for the relatives and friends of the victims was the wall of silence that surrounded the abducted: In hospitals, prisons, and morgues, the searching relatives were told that nothing was known about the fate of the missing. In many cases, they were told that the missing person had probably run off with another woman or abandoned their family to flee to the USA. Days, weeks, months, and finally years of uncertainty passed, during which the relatives remained in an eerie limbo. Former friends and acquaintances no longer greeted each other on the street for fear of being put in contact with the affected family. Second-degree relatives denied their relationship to the missing person; In some cases, even the immediate family tried to conceal the fate of their missing loved one to avoid social isolation. As time passed, the likelihood of the missing person reappearing alive became increasingly slim, yet it was psychologically impossible for the survivors to grieve and process their loss: accepting the missing person’s death and initiating a process of mourning, consolation, and ultimately resolution would feel like a betrayal of the possibly still-living loved one. Furthermore, a new beginning was impossible for many partners of the missing, as they were not officially considered widowed.

A missing person is not simply a political prisoner, nor is it a dead person, although there have been cases where bodies were found for which no one claimed responsibility. Enforced disappearance differs from covert murder because, with the disappearance of the victim’s body, the evidence vanishes as well. Being missing does not mean being dead. Members of relatives’ organizations are therefore demanding the exhumation of secret mass graves, hoping to find the bones and remains of their loved ones and give them a proper burial.

Child Abduction and Forced Adoptions: In Argentina, it was common practice to give children born in prison to abducted and later murdered women to childless military officers’ families. After the end of the dictatorship in 1983, many grandparents and surviving parents tried to find these children. The organization Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo estimates that there are approximately 500 children in Argentina who were abducted by the henchmen of the dictatorship and then secretly given up for adoption. In at least 128 cases, children who disappeared during the military dictatorship were returned to parents or legitimate families by 2018. These efforts are ongoing. Confronting their true origins is usually a very painful process for the now-adult children—not least because their presumed fathers were often involved in the torture and murder of their actual, biological parents.[10] Some of these now-grown children have founded the organization Hijos, which advocates for the harsh prosecution of the perpetrators of that time, regardless of their now mostly very advanced age.

Resistance

In 2005, some of the mothers met with then-Argentine President Néstor Kirchner.

In 1977, the Mothers of the Disappeared founded one of the few open opposition groups against the military dictatorship in Argentina: the Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo). For years, the mothers demonstrated every Thursday in the bustling square in front of the Argentine government headquarters in Buenos Aires, demanding accountability from the government. The participants were repeatedly threatened by the military and were victims of repression and arrests. One of the association’s leaders later explained that they had initially naively believed that the machismo prevalent in Argentina would protect them and that, as older women, they would not be taken seriously as a threat by the military. Early abductions, most notably the disappearance without a trace of founder Azucena Villaflor de Vincenti, shattered these expectations.

Number of Victims

In 1981, Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, declared Central America a “testing ground for the Cold War.” Within a few years, the US-backed military dictatorship in El Salvador murdered approximately 40,000 opposition members, roughly 0.8 percent of the population, many of whom “disappeared.”[11]

Estimates of the number of people who disappeared permanently vary depending on the source. In Chile, the Rettig Commission concluded in 1991 that 2,950 people were murdered or disappeared permanently during the Pinochet regime. In Argentina, the murders of approximately 1,000 people could be proven in detail; the number of people who disappeared permanently during the dictatorship—that is, were almost certainly murdered—was estimated at around 9,000 by the state investigative commission CONADEP and at around 30,000 by human rights groups (see external links). The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported 69,280 people who disappeared or were murdered forcibly between 1980 and 2000. According to the report, paramilitary groups and the government were responsible for approximately 41% of the victims, while the far-left organization Sendero Luminoso was responsible for about 54% of the murders. Human rights organizations estimate that around 45,000 people have disappeared in Guatemala.[12]

Guatemala experienced a near-permanent civil war in the second half of the 20th century, resulting in the deaths of approximately 150,000 to 250,000 people, primarily in massacres of indigenous peoples perpetrated by the army or right-wing paramilitary groups.

Human rights organizations estimate that the overall toll of Latin American repression in the 1970s and 1980s is around 50,000 murders, 35,000 disappearances, and 400,000 imprisonment.[1]

Legal Reappraisal

The Chilean ex-dictator Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 at the instigation of the Spanish investigating judge Baltasar Garzón, but was later released due to political pressure and his “poor health.”

For a detailed discussion of the criminal aspects and the development of international law, see the relevant sections in the article Enforced Disappearances.

Just a few months after the return to democracy, Chile’s newly elected president, Patricio Aylwin, established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in mid-1990. Its purpose was to investigate human rights violations committed between 1973 and 1989, including political assassinations and the disappearance of persons (desaparecidos). Because the military’s influence in the country remained strong, Aylwin was forced to exercise restraint in his approach to addressing the past; prosecuting the crimes would have been unacceptable to the armed forces.[13]

The legal reckoning with these crimes continues to this day in almost all affected countries, or in some cases has only begun in the last few years. This is partly due to the fact that, during the transition to democracy in these countries, amnesty laws protecting the perpetrators were often enacted (see, for example, the Argentine “Closing the Line” law and the Pinochet case), which the military had demanded as a condition for the transition. In some cases, these laws have only recently been repealed, opening up the possibility of prosecuting those responsible. For instance, Jorge Rafael Videla, the first leader of the Argentine junta, was convicted again in December 2010 for numerous crimes committed at that time. The difficulties in prosecution have also contributed to the corresponding development of international law. Such crimes can now be prosecuted internationally, as seen in the International Criminal Court. In particular, the systematic disappearance of people has been explicitly classified as a crime against humanity.

The Latin American human rights movement coined the term “enforced disappearance” in the 1970s. The adoption of the UN Convention against Enforced Disappearances, passed by the UN General Assembly on December 20, 2006, and entering into force on December 23, 2010, is the result of more than 30 years of efforts by relatives of disappeared persons and human rights experts to establish a new criminal offense under international law. A key objective was to extend the concept of victimhood to include family members of disappeared persons in order to guarantee them certain rights.[14]

Among the numerous individuals who have been convicted or are currently on trial are various generals, the former head of the Chilean secret police, Manuel Contreras, and the Argentine officers Adolfo Scilingo, Miguel Ángel Cavallo, and Alfredo Astiz.